Otis Creatives: The Doing - Chapter One

January/February 2026

The Otis Observer is pleased to announce that, over the coming months, we will be publishing selected chapters from The Doing, a new book by local author Eric Bass. In this reflective and thought-provoking work, Bass introduces readers to a solitary figure whose inner life resonates far beyond his island home. As the author himself writes, “Elias, living alone on an island, finds deep and durable meaning and purpose in his life. He reminds us of humankind’s absurd predicament of always searching for something beyond what is already here for us.” We’re delighted to share this work with our readers and to celebrate the creative voices emerging from our own community.

The Doing

Chapter 1 – Elias

Peeking out across the steely green expanse, the sea didn’t care. It never had.

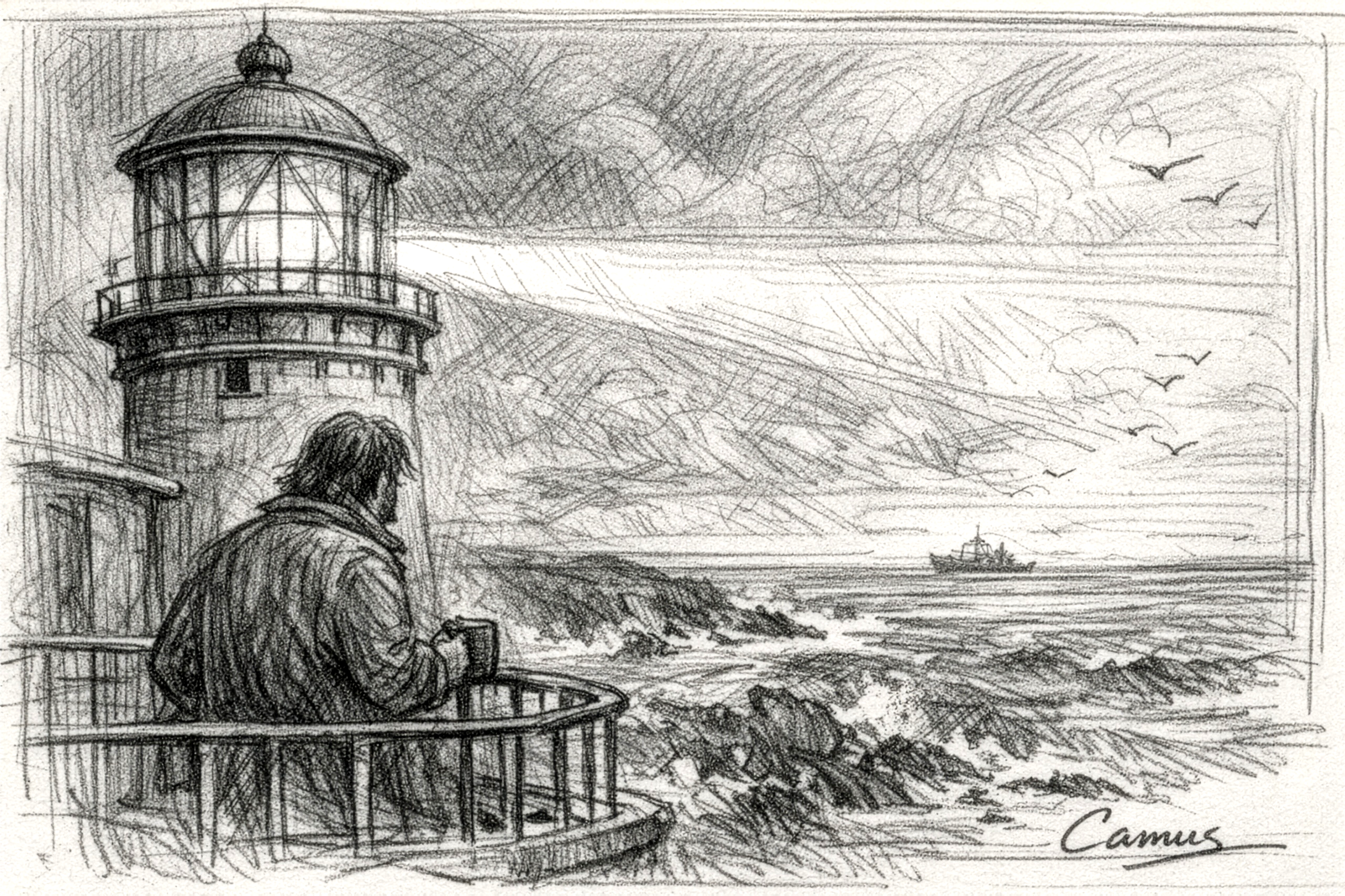

It rolled and hissed against the craggy moss strewn rocks, as if laughing, secretly sneering quietly at everything that tried to matter. Elias Dunning listened to it every morning from the balcony of the ancient lighthouse he manned, perched on a small otherwise tiny barren island 15 kilometers off the coast of Normandy. Standing there, he clutched a brown stained ceramic mug of steaming hot coffee in one hand, the other firmly gripping the black, rusted rail for balance against the sudden wind gusts that could come without warning and lift and destabilize you. Squinting slightly, he looked out, through gentle green eyes framed by a salt weathered face that offered the only hint of his existence. His shoulder-length brown hair stubbornly retained the soft curls of his youth. It never ceased to awaken him, to stir him.

He had lived on Rozven Island for fourteen years. The war had ended, Germany defeated, London, Berlin and the other cities had rebuilt, and men were busy arguing again about progress. None of it reached him. He liked it this way. His world was impenetrable fog, damp stones and imposing eddys, steep steps and the slow heartbeat of the crashing waves.

Each dawn, he lit the commanding lamp at the top of the tower. It reigned atop the chaos, a large mosaic of hand-blown, carefully shaped and assembled glass plates and polished brass taller than he was. What a remarkable feat of craftmanship and engineering. He marveled at how something so delicate and heavy was lifted by men 20 meters atop the stone tower. It wasn’t really a lamp at all; he thought of it as an enormous, focused, pot of fire. Its light beam was meant to guide ships away from the rocks and shores, but ships rarely passed anymore. Nothing much at all passed anymore. The post-war trade routes had shifted. The world, it seemed, had moved on, and the tower had become unnecessary. A relic of the past.

Still, he lit it. Every morning. It shined for 24 hours until he would return once again up the stairs to it again. This had been his daily routine for the past fourteen years since the prior keeper yielded the responsibility to him after four uninterrupted decades. The lamp had an unquenchable thirst that was his job to satisfy. It burned a thick, black, shiny oil delivered to the island twice yearly by a coastal tanker many years past its intended years of service, itself a remnant of the war. On these occasions, he grabbed the pump’s iron handle and using his weight and powerful arms, he coaxed the liquid from the boat into the squat red and white painted tank that bulged out from the tower base.

He told himself it was his duty, but deep down, he knew it was more than that. There was something in the act itself. The simple, daily routine of lighting, cleaning, polishing kept him alive. It sustained him. Checking the fuel lines for cracks and performing minor repairs when needed. The unrelenting coldness of deep winter could clog the fuel intake and choke the lamp while he slept. It was the kind of work that made no sense and yet ironically made everything bearable.

Sometimes he imagined a tall Schooner far out at sea, a weathered old Captain or First Mate at the helm catching sight of his light and turning safely away. Splendid ships ferrying brave men, traders and explorers. But he knew it was a fantasy. There were no weathered weary sailors. There were no more explorers. Only unsightly square barges ferried steel boxes to waiting ports. The only eyes that saw his work were the hungry seagulls, porpoises chasing herring, and the dark, moody sky. Rarely, on bright moonlit nights, no one could see the light or would even have need for it. Seamen looked skyward for navigation.

He often wrote in the large leather-bound Keeper’s logbook, though there was no one to read it. The words “Journal du phare” embossed in large gold letters across the cover. Another irony. His notes had grown strange over time. They were less about weather, more about his innermost thoughts and deliberations. Mostly nonsensical thoughts. After laying his pen down, he lacked the courage to read them.

“Clear morning. No wind. The sun rose again for no reason.”

“The lamp burns, though no ship watches. It makes no difference.”

He didn’t pray. He didn’t believe. But he felt something close to reverence when the light finally reached full bloom and brightness. It cut through the fog like a blade. It was absurd, of course: caring so deeply about something. How ridiculous. He didn’t know why he cared at all. His professors would surely find this amusing. They’d abuse him. He shook his head slightly at the thought. Still, he clung strongly to it without reason. Perhaps that was the only kind of faith left. He lingered on the thought and then let it go.

Some nights, when the dense fog pressed close against the windows, like it was seeking to find its way inside, and the motion of the sea went silent, he wondered if he was already dead. Maybe the afterlife was just this. Eternal mindless repetition. Feeling alone amid the grey mist disturbed neither by voices nor songs.

Then morning came again, and he climbed the steep steps, carefully orchestrating all the tasks required to light the lamp, make it roar, and watched the sea. The work continued. And that, somehow, and very strangely, was enough.